Prologue

Graeco-Roman Antiquity in the New World

The Academia de San Carlos in the heart of Mexico City is an institution of extraordinary cultural and historical significance. Its foundation in 1783 is closely linked to Mexico's colonial history and the cultural policy of the Spanish Bourbon kings Charles III and Charles IV. In its more than 240-year history, which directly reflects Mexico's political development, it has served as an important place of work and training for artists.

In addition to books , prints and other media, the Academy houses the oldest collection of plaster casts of ancient and modern sculptures on the American continent. These works have been imported from Europe in several shipments since the institution was founded. They not only served as models and as representatives of a canon of exemplary sculptural forms but also contributed from the outset to spreading the ideals of the Enlightenment and Classicism in the New World.

European institutions such as the Academia de San Fernando Madrid, Facade of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, situated in the Palacio de GoyenecheCol. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid in Madrid apparently served as a model for the new colonial foundation which was based on the cultural policy schemes of the Spanish crown. Established knowledge and cultural models were transferred to the colony in the form of plaster casts, books and prints.

in Madrid apparently served as a model for the new colonial foundation which was based on the cultural policy schemes of the Spanish crown. Established knowledge and cultural models were transferred to the colony in the form of plaster casts, books and prints.

We are confronted with one of numerous Roman copies of what appears to have been a famous Greek bronze work from the 2nd century BC, which included a nymph, of whom many replicas have likewise survived. The scene seems to have depicted an "Invitation to the Dance" (as the modern archaeological term puts it). The female figure sat on a rock with her bare chest exposed and a mantle around her hips, her legs crossed, taking of one sandal, and laughing in the satyr’s face. The satyr was also characterized by a cheerful expression, with unruly hair, a snub nose, pointed ears, and a ponytail at the back.

The original group was evidently famous in antiquity, and it might have stood in Asia Minor, because around 200 CE it still appeared on coins from Cyzicus, a city on the Sea of Marmara. While the original work might have served as a votive offering in a sanctuary, the Roman copies adorned the villas and homes of the elite or were part of the sculptural decoration of public baths. In such settings, the group was meant to evoke a cheerful and erotic atmosphere.

SF Col. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

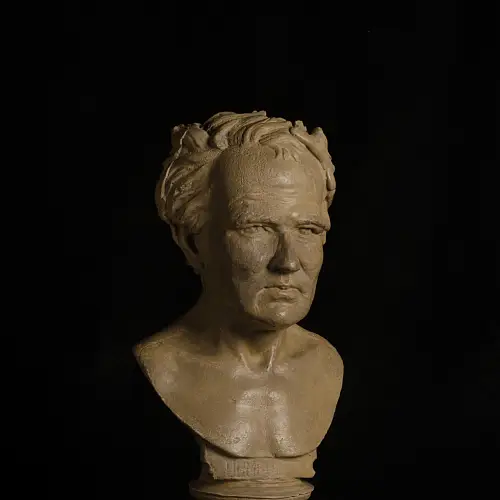

Historical sources can be used to trace the ideas and achievements of the artists involved, especially Jerónimo Antonio Gil and Manuel Tolsá , who were involved in the founding of the Academia. In order to understand the historical dimension of the institution, contemporary perceptions of Mexican history and culture, such as those of Alexander von Humboldt , are also instructive.

SF

Before the Foundation of the Academia de San Carlos

Classical Learning in Mexico

VFM https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/ff/Antiguo_Convento_de_Santiago_Tlatelolco%2C_patio.JPG, Foto: Raymundo Perera

From the first years after the conquest of Mexico in 1521, European missionaries founded schools in the new territories where Latin and the humanistic tradition were the basis of education. In the beginning, in centres such as the Colegio de la Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, organized by the Franciscans, the ancient Aztec elite was educated in the European canon of knowledge, especially with the aim of preserving and transmitting the knowledge of the indigenous people in Latin and Spanish, but at the same time to instruct them in Catholic theological doctrines and colonial cultural norms. Pedro de Gante (1486-1572) and Bernardino de Sahagún (1500-1590) stood out in this field.

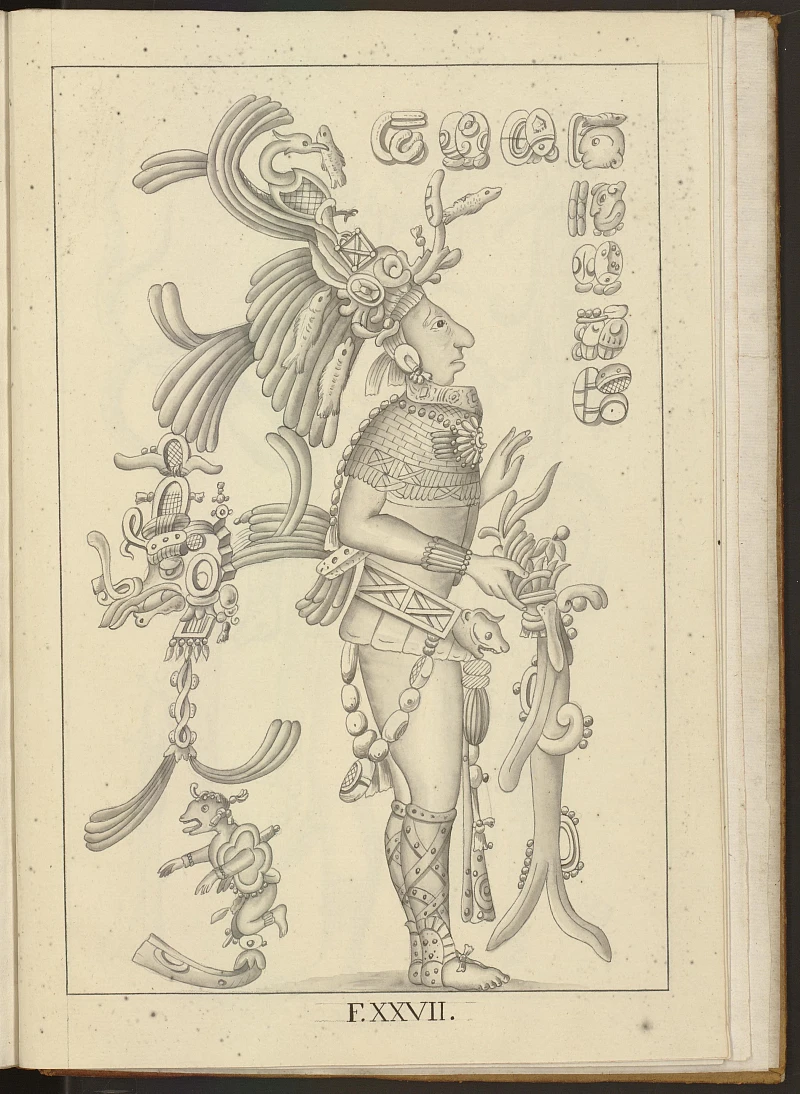

VFM https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/9531903b-f24c-fc52-e040-e00a18062b67

With the arrival of the Jesuits in New Spain in the second half of the 16th century, the order took a leading role in teaching in the Mexican territories. Medicine, law, theology and literature were most important. Latin and Spanish were the languages of education. At the base of the different disciplines, there was a wide canon of authors that students had to read, from Cicero, Virgil and Ovid, to late antique and medieval Christian authors, to contemporary humanists. Rich libraries were quickly formed in cities such as Mexico, Oaxaca and Puebla; European books were constantly arriving in New Spain, and books were being published and printed here. too. The peak of classical studies in Mexico occurred in the 18th century. The Colegio Máximo de San Pedro y San Pablo and the Colegio de San Ildefonso in Mexico City, as well as the Colegio de San Francisco Javier in Tepotzotlán, were centers where generations of secular and religious students were educated.

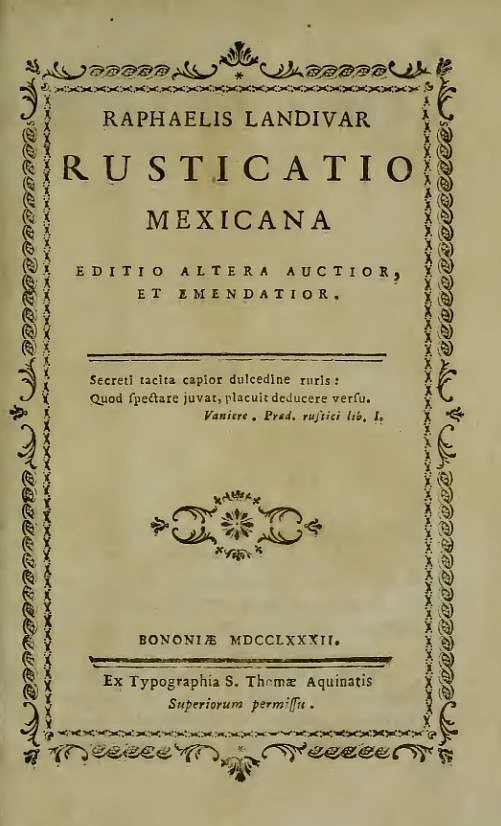

VFM https://archive.org/details/raphaelislandiva00land/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater

However, the near monopoly that the Jesuits exercised in education, and the influence that this had not only in New Spain, but in the entire Hispanic and Catholic world, led to the expulsion of the order from all Spanish dominions in 1767 by orders of Charles III Manuel Ocaranza, Tondo with portrait of King Charles III of Spain, 1875-1881, Mexico City, Academia de San Carlos, Galería CentenarioCol. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC , and even to the temporary suppression of the order by papal decree in 1773. On the one hand, the government of Charles III hoped to reaffirm its influence in the formation of its territories, introducing enlightened ideas; on the other hand, the exiled Jesuits published an important number of works highlighting their regional pride. In particular, characters such as Francisco Xavier Clavijero, Pedro José Márquez, Francisco Xavier Alegre or Rafael Landívar, published important works in Europe at the end of the 18th century that contributed to the development of a spirit of national identity that anticipated the independence movements in Latin America at the beginning of the 19th century.

, and even to the temporary suppression of the order by papal decree in 1773. On the one hand, the government of Charles III hoped to reaffirm its influence in the formation of its territories, introducing enlightened ideas; on the other hand, the exiled Jesuits published an important number of works highlighting their regional pride. In particular, characters such as Francisco Xavier Clavijero, Pedro José Márquez, Francisco Xavier Alegre or Rafael Landívar, published important works in Europe at the end of the 18th century that contributed to the development of a spirit of national identity that anticipated the independence movements in Latin America at the beginning of the 19th century.

VFM Museo Nacional de Arte de México (MUNAL) https://munal.emuseum.com/objects/395/retrato-de-jose-de-ibarra?ctx=63a9bec2-4390-454c-bbfa-7f7373df672c&idx=0

On the other hand, painting and sculpture developed within the organisational framework of guilds, first with artists coming from Europe, and later with local artists trained in the New Spanish workshops. The most frequently represented themes were religious. Painters such as Juan Correa (1646-1716), Cristóbal de Villalpando (1649-1714), José de Ibarra (1685-1756) and Miguel Cabrera (1695-1768) stand out as the most influential painters in New Spain in the generations that preceded the formation of the Academia de San Carlos.

The large painting depicted here takes up elements from chapter 12 of the Apocalypse of John, in particular the vision introduced by the phrase "signum magnum apparuit in caelo" (“a great sign appeared in heaven” Apoc 12.1): on the right-hand side, the evangelist pronounces the Latin phrase. Mary appears in the center, backed by the sun, the moon beneath her feet and a crown of twelve stars around her head; it is therefore the Virgin of the Apocalypse, a pictorial theme that enjoyed particular esteem in New Spanish Catholic society.

The Virgin hands her son to the heavenly Father, who in turn gives her two eagle wings so that she can flee into the desert. The left half of the picture also depicts the great cosmic war between the archangel Michael and the seven-headed dragon. The monster is thrown to the earth. Mary steps on the head of the monster, while on the left a group of angels present objects symbolizing the immaculate nature of the Virgin.

VFM https://munal.emuseum.com/objects/358/la-virgen-del-apocalipsis?ctx=438c11e8-98c4-4fb3-a361-ff441cdd1214&idx=0

VFM

From the Spanish Colonial Era to Mexico's Independence

A Very Brief History of the Academia de San Carlos

From the time Spain conquered Mexico by force in the 16th century, the study of the Latin language and the reception of Graeco-Latin culture played an important role in the colony. The European clerics who soon arrived founded educational establishments in the humanist tradition , in which the study of the Latin language was central. Over the next two centuries, education remained in the hands of Catholic orders, above all the Jesuits.

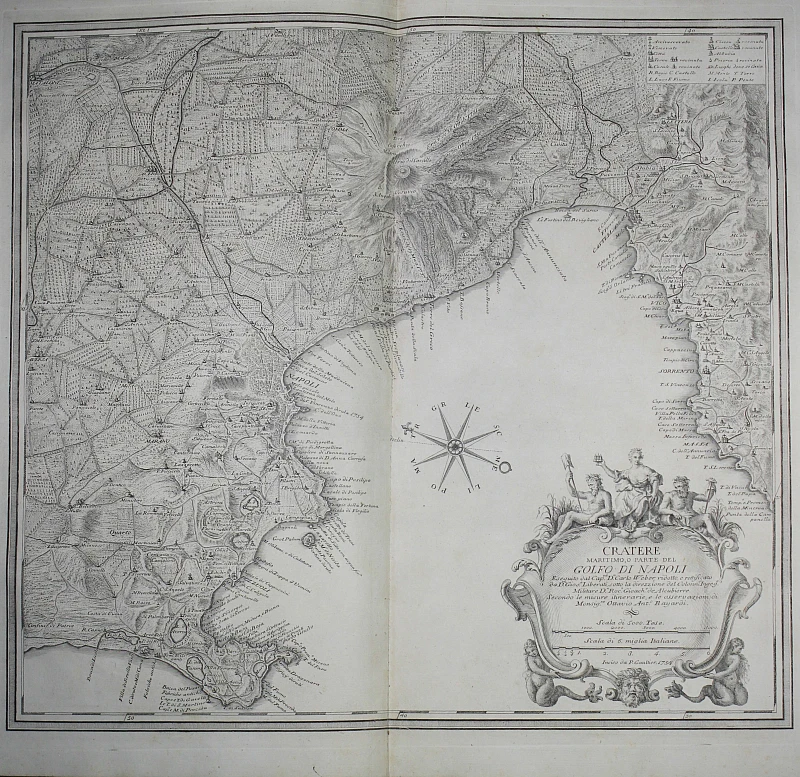

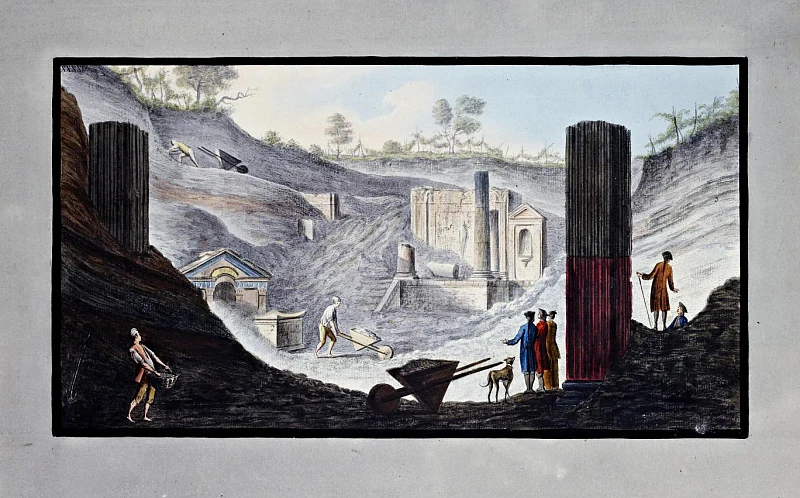

In the course of the Enlightenment, the state took over the monopoly on education, and the frame of reference of classical antiquity was redefined. This was not least due to the excavations in Pompeii and Herculaneum, which were sponsored by the Bourbon King Charles VII of Naples from 1738 and 1748 respectively. The rich finds, such as wall paintings and sculptures, changed the view of the Graeco-Roman past and inspired the enlightened elites in culture and politics.

As a pioneer of modern archaeology, Weber also made significant contributions to the research and documentation of the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum, which was discovered in 1750 and excavated using tunnels. The expansive Roman villa by the sea is famous for the charred papyrus scrolls found in one of its rooms and for its rich collection of sculptures made of bronze and marble. Weber hardly received recognition for his work during his lifetime. For example, he was denied entry into the Accademia Ercolanese (founded in 1755). However, Johann Joachim Winckelmann later praised him for his careful working methods in his "Letter and Report on the Discoveries at Herculaneum" (Dresden 1762).

SF Col. Biblioteca Nacional de México, Fondo Academia de San Carlos, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

Sir William Hamilton (1730-1803), whose publication on volcanoes includes the Pietro Fabris’ study of the early excavation of the sanctuary, served as the British envoy to the Bourbon court in Naples from 1764 to 1799. In addition to his volcanological research, the diplomat was deeply engaged with Graeco-Roman antiquity and its material remains. He assembled an extensive collection of antiquities, including numerous Greek vases of high quality, which he had published by Pierre-François Hugues d’Hancarville (Collection of Etruscan, Greek and Roman Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Honble. Wm. Hamilton, Naples 1767–1776). This work sparked a widespread enthusiasm for classical antiquity, as artists as well as artisans adopted the illustrated motifs and ornaments as models for their own creations of decorative objects in ceramics, furniture, textiles etc.

SF https://archive.org/details/gri_33125009359809/page/n164/mode/1up?view=theater

On his accession to the Spanish throne as Charles III Francisco Tomás Prieto, Medal with portrait of Charles III of Spain, 1770 (plaster cast, 1790, Antigua Academia de San Carlos, FAD/UNAM), 21.5 x 17 cmCol. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC in Madrid in 1759, King Charles brought his ideas of an exemplary antiquity back to his homeland. He also wanted to extend his educational policy based on such ideas to the American territories, especially New Spain. After the expulsion of the Jesuits from all Spanish territories (1767), which was intended to eliminate the order's great influence on education and politics, Charles decreed the foundation of an art academy in the colony, the Royal Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City (1783). Its patron saint was Saint Charles Borromeo, Bishop of Milan from 1564 to 1584, who had formulated a reform program for the architecture and decoration of churches during the Counter-Reformation.

in Madrid in 1759, King Charles brought his ideas of an exemplary antiquity back to his homeland. He also wanted to extend his educational policy based on such ideas to the American territories, especially New Spain. After the expulsion of the Jesuits from all Spanish territories (1767), which was intended to eliminate the order's great influence on education and politics, Charles decreed the foundation of an art academy in the colony, the Royal Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City (1783). Its patron saint was Saint Charles Borromeo, Bishop of Milan from 1564 to 1584, who had formulated a reform program for the architecture and decoration of churches during the Counter-Reformation.

VFM https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/698801

Modelled after the Royal Academy of San Fernando in Madrid, the new institution was intended to ensure the training of architects, painters and sculptors in line with neo-classicist ideals. The central founding figures were the medalist and engraver Don Jerónimo Antonio Gil (1731-1798), the sculptor Manuel Tolsá (1757-1816) and the painter Rafael Ximeno y Planes (1759-1825). Tolsá in particular is credited with building up the collection of casts which he brought along from Spain and which served as didactic material.

Initially housed in a building of the Royal Mint (Real Casa de Moneda) in the centre of Mexico City, due to the large number of students the Academia de San Carlos moved to the nearby former Hospital Real del Amor de Dios in 1791, which had been closed in 1786.

As a consequence of the Mexican War of Independence (1810-1821), the academy remained closed for a long time. It was not reopened until 1847 as the National Academy of San Carlos on the initiative of the controversial president Antonio López de Santa Anna. In 1857, Francesco Saverio Cavallari (1809-1896), until then director of the Milan Academy of Arts, took over the management of the Mexican institution. He was also responsible for the redesign and renovation of the existing academy building. Its architecture combines the European neo-Renaissance style with elements typical of the country, such as local volcanic stone. During this time, the Catalan sculptor Manuel Vilar (1812-1860) expanded the academy's plaster collection by acquiring casts, mainly from Italy, where he had studied.

Buen Abad had studied painting at the academy himself and later worked as a photographer and lecturer. In addition, he participated in the 1889 Paris Exposition as a member of the Mexican delegation, where he was awarded a bronze medal for his works.

SF Col. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

The collection grew further in the early 20th century when the Mexican architect Antonio Rivas Mercado (1853-1927) became director. Thanks to his excellent relations with the Academy of Fine Arts in Paris, he further expanded the collection of casts and procured copies of important works from Paris. He was also responsible for the construction of the large glass dome over the central courtyard of the Cavallari building (1912-1913).

With the Mexican Revolution (1910-1921), the academy once again experienced a phase of instability. Classicism had long since lost its significance as a cultural reference model. Artists no longer wanted to be guided by ancient works but by the reality of the people's lives. Artists such as Diego Rivera (1896-1957), José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974), the “big three” of Mexican muralism, had studied at the academy and were now fighting for an art education that aimed for social justice. The director of the academy during these years, the famous painter Gerardo Murillo (1875-1964), known as Dr. Atl, even removed the study of plaster casts from the curriculum in order to focus on real life as a model to imitate.

In the 1920s, the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes (National School of Fine Arts) was integrated into the University of Mexico (UNAM). Its current institutional heirs are the Faculty of Architecture and the Faculty of Art and Design which is housed in the Academy building. In recent decades, enormous efforts have been made to enhance, preserve and communicate the academy's heritage and history, as well as its collection of casts, and to exploit its potential.

VFM

Neoclassicism as a Program

Cultural policy under the reign of Charles III of Bourbon

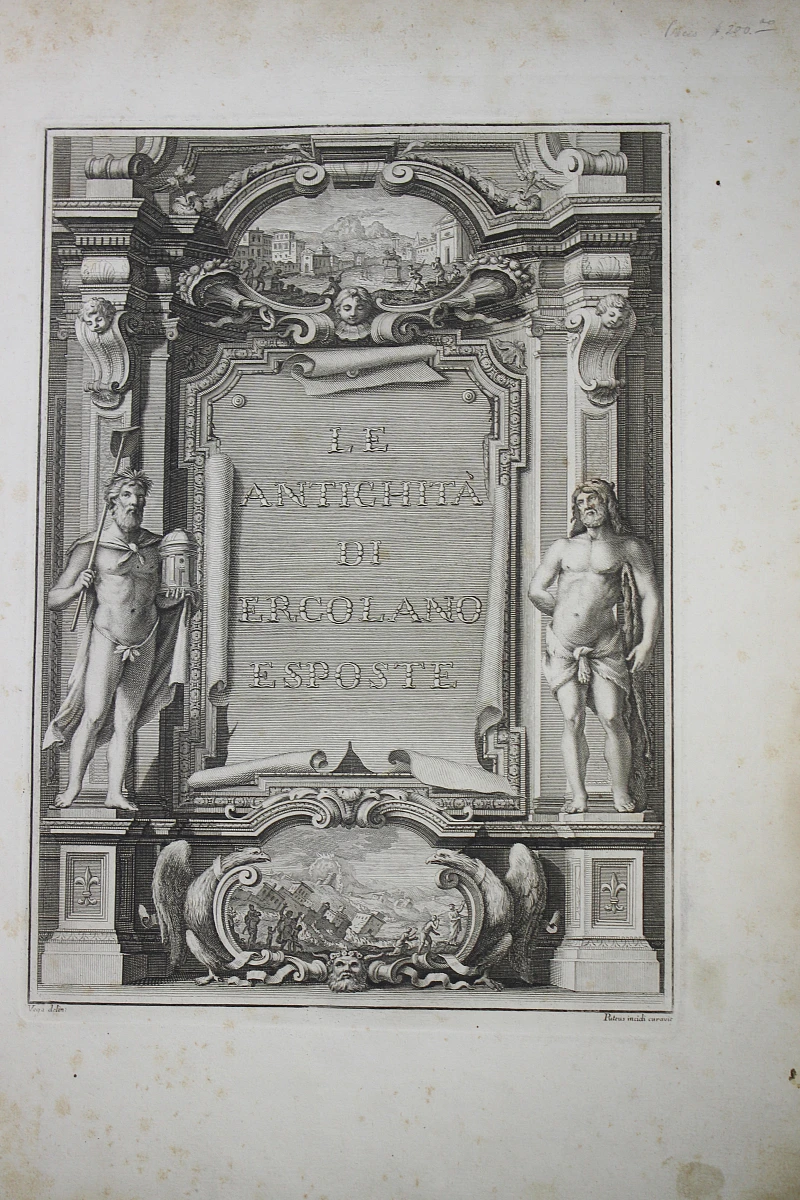

During the reign of Charles III Bourbon over Spain and its colonies (1759-1788), the implementation of the ideas of the Enlightenment and the associated artistic and scientific exploration of classical antiquity played an important political role. Already in his youth as Duke of Parma and Piacenza, he inherited the famous antiquities collection of the Farnese family, from which his mother descended. As King of Naples and Sicily (1735-1759), Charles, supported by his minister Bernardo Tanucci, not only initiated numerous reform projects, but also arranged the first systematic excavations at the ancient sites of Herculaneum, Pompeii and Stabiae around mount Vesuvius (from 1738, 1748 and 1749, respectively). The finds such as sculptures, wall paintings, papyri were exhibited and restored in the Museum Herculanense in the royal summer residence of Portici; in 1755 the Accademia Ercolense was founded which published the magnificent volumes of the Antichità di Ercolano Esposte from 1757.

VFM Col. Biblioteca Nacional de México, Fondo Academia de San Carlos, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

From Madrid, Charles attempted to renew the Spanish state administration, which was considered somewhat backward, and this included cultural policy measures. He appointed the painter Anton Raphael Mengs Anton Raphael Mengs, Self-portrait, 1773, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, oil on panel, 93 x 73 cmhttps://de.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Mengs,_Selbstbildnis.jpg to his court as a promotor of classicism, turned the Royal Library (with its own printing press) and the academies of art into important centres of learning by promoting the Academia de San Fernando Madrid, Facade of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, situated in the Palacio de GoyenecheCol. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid

to his court as a promotor of classicism, turned the Royal Library (with its own printing press) and the academies of art into important centres of learning by promoting the Academia de San Fernando Madrid, Facade of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, situated in the Palacio de GoyenecheCol. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid and establishing similar institutions in Valencia (1768) and Mexico City (1783) based on its model. The foundation of the Academia de San Carlos in New Spain was intended to bring about an aesthetic reorientation of coinage, art, crafts and architecture from Baroque to Classicism and at the same time contribute to the revival of trade. The enlightened state policy was also intended to break the church's monopoly on education, especially that of the Jesuits who were expelled from all Spanish territories in 1767. In addition, Charles III supported the early exploration of Palenque, an ancient Mayan city in south-eastern Mexico, thus creating the basis for preserving the Prehispanic heritage.

and establishing similar institutions in Valencia (1768) and Mexico City (1783) based on its model. The foundation of the Academia de San Carlos in New Spain was intended to bring about an aesthetic reorientation of coinage, art, crafts and architecture from Baroque to Classicism and at the same time contribute to the revival of trade. The enlightened state policy was also intended to break the church's monopoly on education, especially that of the Jesuits who were expelled from all Spanish territories in 1767. In addition, Charles III supported the early exploration of Palenque, an ancient Mayan city in south-eastern Mexico, thus creating the basis for preserving the Prehispanic heritage.

VFM https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbc0001.2005kislak1/?sp=51 Digital ID: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.rbc/kislak.74394.1

SF

From the Collection of an Artist

The Painter Anton Raphael Mengs and the Academia de San Fernando in Madrid

The cast collection of Anton Raphael Mengs

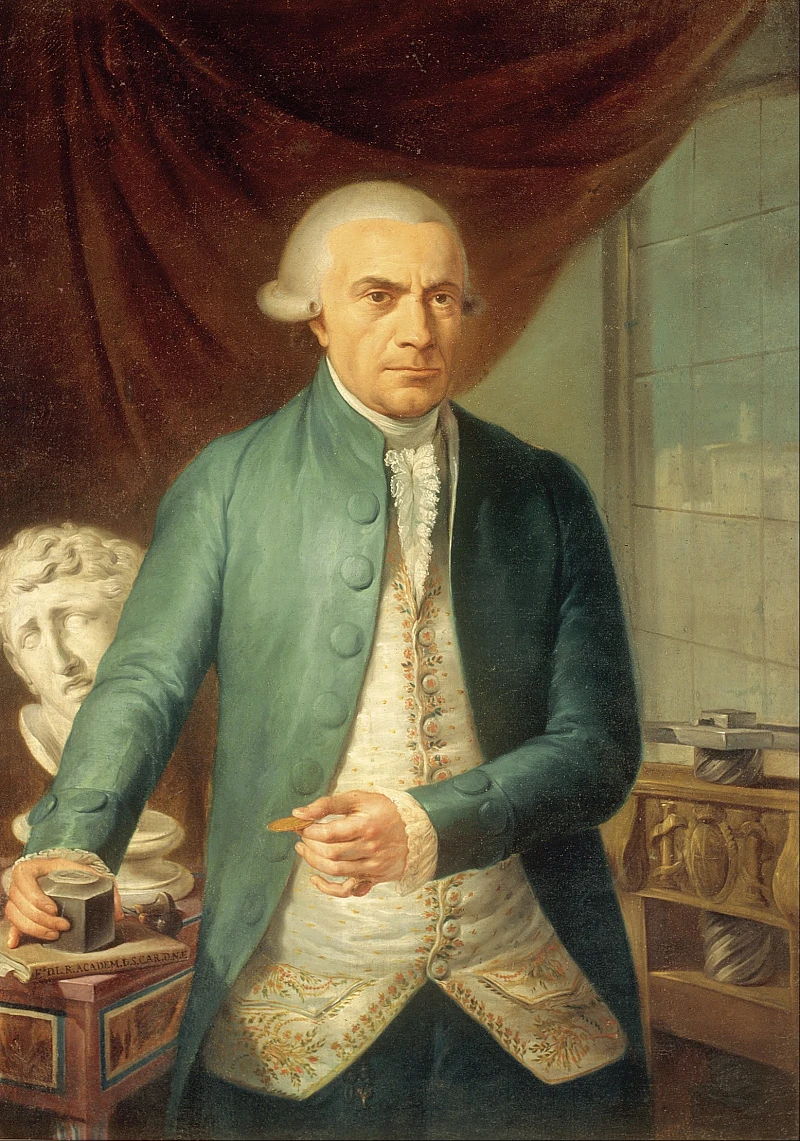

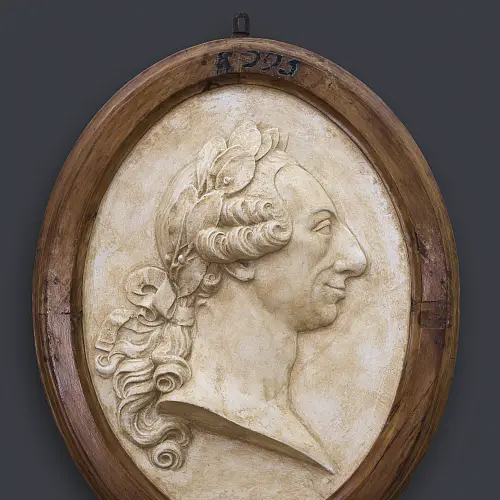

The painter Anton Raphael Mengs (1728-1779) is considered a pioneer of classicism. Having grown up in Dresden, he came to Rome for the first time at the age of 12. Later in his life, he would come back to the eternal city for long periods, and finally die there. Due to his artistic achievements, he was appointed court painter to the Saxon Elector and Polish King August II/III, and he also gained the esteem of the Russian Tsarina Catherine II and the Roman Cardinal Alessandro Albani, who sponsored him in particular. In 1761, Charles III Camillo Paderni, Portrait of Charles VII/V of Naples and Sicily, in: Le Antichità di Ercolano esposte. Le pitture antiche d'Ercolano e contorni incise con qualche spiegazione. First Volume (Naples 1757), engravingCol. Biblioteca Nacional de México, Fondo Academia de San Carlos, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC of Spain appointed him to the Spanish court to work alongside Giambattista Tiepolo on the ceiling frescoes of the royal palace in Madrid.

of Spain appointed him to the Spanish court to work alongside Giambattista Tiepolo on the ceiling frescoes of the royal palace in Madrid.

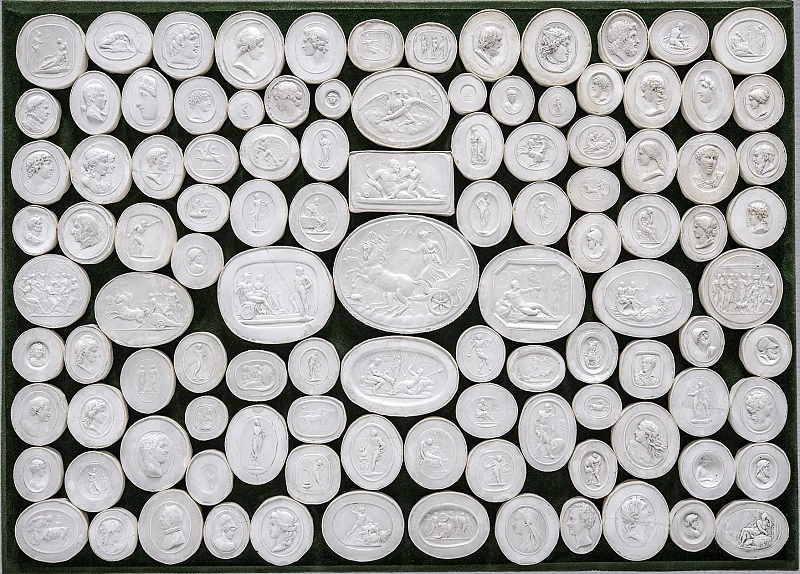

Mengs shared the artistic ideal of classical antiquity with his friend Johann Joachim Winckelmann. From his second stay in Rome (from 1752), he therefore built up an extensive collection of plaster casts of Graeco-Roman and modern sculptures, eventually comprising many hundreds of objects. These copies were not only used by the painter in his studio for his own engagement with exemplary works, such as his reconstruction of the Pasquino Group. Rather, he also employed them as models in the instruction of his students in order to train their drawing skills and good taste.

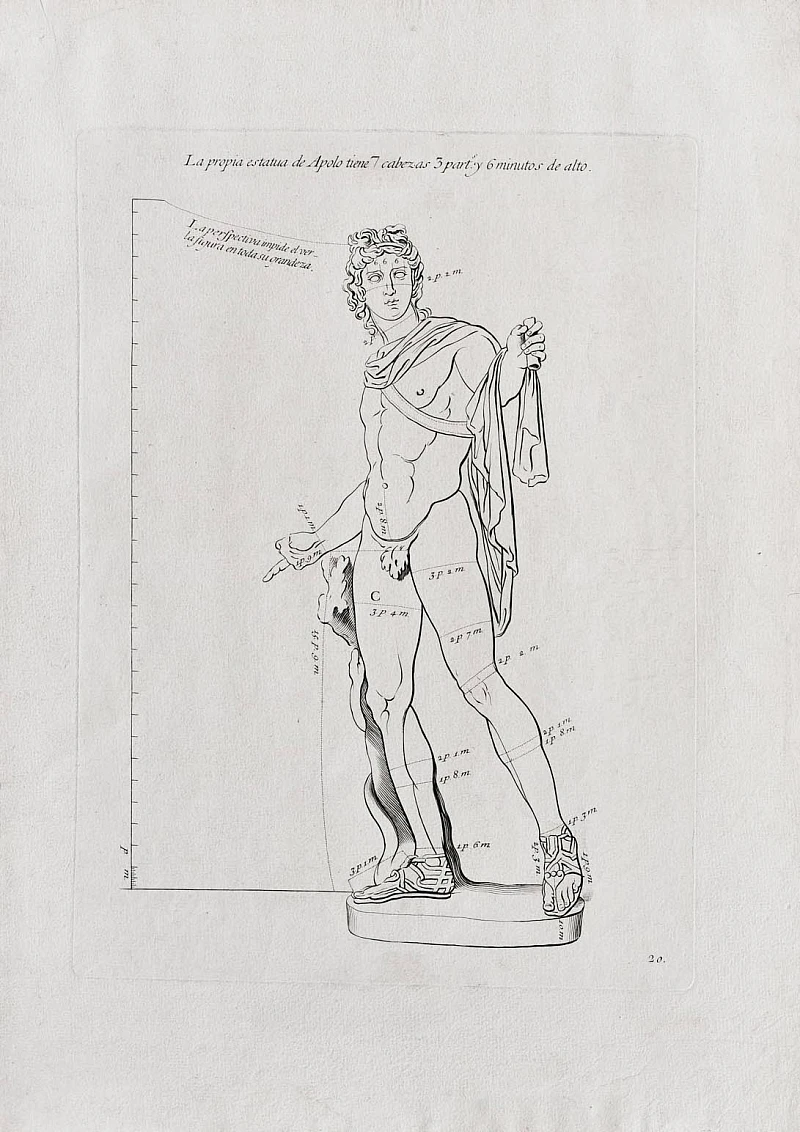

After the sculpture was discovered at the end of the 15th century in Anzio (Antium), a Roman villa area in Latium on the Tyrrhenian Sea, it was acquired in 1510 by the Renaissance pope Julius II (pope from 1503-1513) and set up in the Cortile delle Statue in the Vatican. Since Michelangelo's time, it has served as a model for artists and was especially highly regarded in the 18th century. Johann Joachim Winckelmann considered it the highest ideal of art among all works of antiquity, which significantly informed his Neoclassical aesthetic principles. Similarly, Anton Raphael Mengs, who once owned the plaster cast at Dresden, engaged with the Apollo of the Belvedere: In his painting Perseus and Andromeda (ca. 1775, St. Petersburg, Hermitage), the artist varied the statue's pose to depict the Greek hero.

SF Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Foto: Elke Estel/Hans Peter Klut

In Mengs' time, the procurement of plaster casts was still a major challenge, because there were no specialized workshops and the aristocratic owners strictly monitored the accessibility and availability of their collections. However, thanks to his good contacts with the protagonists of the Roman art market, including the sculptor and restorer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, and with the noble houses of Italy, the painter succeeded time and again in obtaining permission to make casts. In 1770, for example, the Grand Duke of Tuscany allowed him to make casts of important works in Florence. As early as 1768, Mengs got his hands on the first casts from new molds of famous works in the Vatican.

SF

Mengs and the Academia de San Fernando

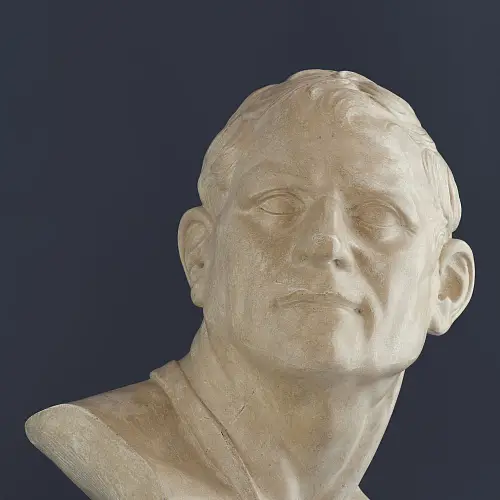

The creator of the bust, Giovanni Domenico Olivieri (1708–1762), originally from Italy, not only served as the king's first sculptor but was also directly involved in the establishment of the Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid. From 1752 onward, he taught there as the director of sculpture.

SF Col. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid, Foto: RABASF

VFM Col. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid, Foto: RABASF, Carlos Manso y Pablo León

As a result of his appointment as Spanish court painter, Anton Raphael Mengs was given the title of Honorary Director of Painting at Madrid's Real Academia de las Tres Nobles Artes de San Fernando (now the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando), the royal academy of art, which had been founded by King Philip V in 1744 and opened by Ferdinand IV in 1752. Its modest collection of plaster casts was expanded in 1776 with casts from Mengs' collection in Madrid which he donated to the academy via Charles III before returning to Rome due to illness. At the same time, the king gave the institution moulds of ancient works that had been excavated in Pompeii and Herculaneum during his reign over the Kingdom of Naples. In 1779, in the last year of his life, the painter also arranged for a large number of plaster casts (some of them newly made) from his studio to be shipped from Rome to Spain, packed in 76 crates. Somewhat later, 24 crates of moulds that Mengs had been allowed to take in Florence in 1770 and which remained there were transported to Madrid.

The group, just under 90 cm in height, impresses with its intricate composition of athletes tightly intertwined in a struggle on the ground. It apparently represents the Greek pankration, a discipline that included both boxing and wrestling, where nearly everything was allowed – except biting and eye gouging.

SF Col. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

SF Foto: Wolfgang Fuhrmannek, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt, CC BY-SA 4.0

Nevertheless, a huge collection remained in Rome, the majority of which – 883 objects – were purchased by the Saxon court at Dresden three years after the artist's death. With the help of Mengs' moulds and casts in Madrid, the sculptor Manuel Tolsá in turn created his extensive supply of plaster copies for the newly founded Academia de San Carlos in Mexico City in 1790. Therefore, the Mexican institution was not only based on the model of the mother country in terms of ideas and founding staff but also as regards its teaching materials.

SF

Laocoon in Mexico

The Plaster Cast Collection of the Academia de San Carlos in the Spanish Colonial Era

Plaster casts were an important teaching tool for artistic training in the Neoclassical movement of the 18th century. Since the foundation of the academies, plaster sculpture collections allowed artists to engage with the Classical canon of beauty in order to develop their drawing skills and, more generally, develop ‘good taste’ (buen gusto). Jerónimo Antonio Gil , the founding Director-General of the American academy, was a key figure in the arrival of the plaster casts in New Spain. He took along a small collection of casts, when he came to the country in 1788 but “only four or five heads” survived the transport. Therefore, in the following years he requested further plaster copies from the authorities, and in 1785, he addressed the Junta Superior de Gobierno, the Superior Government Board of the Academy, to request the purchase of plaster casts from the Academy of San Fernando at Madrid in order to equip the New Spanish academy with a comprehensive teaching collection. Gil requested, as a start, plaster casts of: “a large Apollo cast from the Academy [in Madrid], another [cast] of the Medici Apollo, another of Venus de’ Medici, another of Laocoön, another of Castor and Pollux [i.e. the Ildefonso Group], another of Hercules [Farnese], and a series of the best heads, feet, hands, and bas-reliefs.”

At Madrid, Manuel Tolsá , who had successfully applied for the position of Director of Sculpture in 1789, was ordered by the king to select the works of art and to oversee the transport of the plaster casts to the viceroyalty. He was assisted by the plaster molder at the Madrid Academy, Josef Panucci. On the whole, 192 pieces were selected, including 70 complete sculptures, 51 reliefs, and 71 heads, most of which were casts of ancient works. Among these plaster casts are notable sculptures that are still preserved at San Carlos, such as Laocoön and his Sons Group of Laocoon, plaster cast, 1790, Mexico City, Antigua Academia de San Carlos (FAD/UNAM)The original Laocoön group has been in the Vatican Museums since its discovery on the Oppian Hill in Rome more than 500 years ago. The sculpture was made of marble in the late 1st century BCE and depicts the Trojan priest Laocoön and his two sons being attacked at an altar by two giant serpents. The animals coil around the arms and legs of their victims, binding them together in this way. The boys and their father are arranged in a single plane. This leads to a single perspective from which the dramatic scene can be perceived. According to the mythological tradition, made famous above all by Virgil's Aeneid (Book 2.40-56; 199-234), Laocoön is a priest of Apollo or Poseidon. The suffering that befalls him and his sons is explained in various ways in ancient literature. According to one tradition, Laocoön enraged Apollo by having intercourse in front of his cult statue (according to the Hellenistic author Euphorion, as quoted by Virgil's commentator Servius: ad Aen. 2.201), or that he warned his fellow citizens about the danger of the Trojan Horse against the will of the gods (cf. Virgil, Aen. 2.199-234). One message of the group is that not even by retreating to the altar the father and his sons can be saved from divine power. In this way, the ancient spectator was confronted with the helplessness of human existence in the face of greater forces.

The original in the Vatican can be identified with a group that Pliny the Elder mentions around 70-79 CE in a residence of the Flavian prince Titus (Plin. nat. 36.37). According to him, Laocoön is an exceptional work by the sculptors from Rhodes Hagesandros, Polydoros, and Athenadoros. The Roman author seems to suggest that it was made from a single block of marble, but in reality, the three artists assembled it from at least seven pieces, with the joints carefully concealed. Originally, the right arm of the central figure was bent, as is demonstrated by a fragment rediscovered only in 1903 by the archaeologist and art dealer Ludwig Pollak in a stonemason’s workshop on the Esquiline Hill. Therefore, the copy created around 1790 in the Academia de San Carlos includes the old restauration showing an extended arm.

As a masterpiece of ancient sculpture and a valuable possession of the papal collections, the artwork has exerted an enormous artistic and scholarly impact in Europe and beyond since the early modern period. The expressive visual language inspired numerous painters and sculptors to engage with the sculpture. Copies in bronze and marble served as ornaments for palaces and gardens. Additionally, plaster casts were used as models in academic drawing classes. Especially in the Age of Enlightenment and Neoclassicism, i. e. the 18th century, the group became the focal point of aesthetic theories developed by intellectuals such as Johann Joachim Winckelmann and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing.

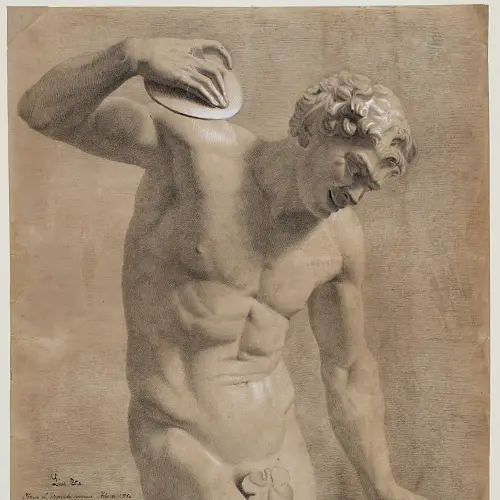

SFCol. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC , the Satyre Satyr playing the footclapper (kroupezion), plaster cast, 1790, Mexico City, Antigua Academia de San Carlos (FAD/UNAM)The cast is from a small-scale marble statue in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence (Inv. 220, height 1.43 m), which was formerly owned by the Medici family and was heavily restored in the 16th century, particularly regarding the head and arms. The statue depicts a satyr from the retinue of Dionysus, the god of wine. The naked figure taps a footclapper (kroupezion in Greek, worn like a sandal) in order to mark the rhythm, bending forward and raising its arms. Originally, the figure either snapped its fingers or played small cymbals.

, the Satyre Satyr playing the footclapper (kroupezion), plaster cast, 1790, Mexico City, Antigua Academia de San Carlos (FAD/UNAM)The cast is from a small-scale marble statue in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence (Inv. 220, height 1.43 m), which was formerly owned by the Medici family and was heavily restored in the 16th century, particularly regarding the head and arms. The statue depicts a satyr from the retinue of Dionysus, the god of wine. The naked figure taps a footclapper (kroupezion in Greek, worn like a sandal) in order to mark the rhythm, bending forward and raising its arms. Originally, the figure either snapped its fingers or played small cymbals.

We are confronted with one of numerous Roman copies of what appears to have been a famous Greek bronze work from the 2nd century BC, which included a nymph, of whom many replicas have likewise survived. The scene seems to have depicted an "Invitation to the Dance" (as the modern archaeological term puts it). The female figure sat on a rock with her bare chest exposed and a mantle around her hips, her legs crossed, taking of one sandal, and laughing in the satyr’s face. The satyr was also characterized by a cheerful expression, with unruly hair, a snub nose, pointed ears, and a ponytail at the back.

The original group was evidently famous in antiquity, and it might have stood in Asia Minor, because around 200 CE it still appeared on coins from Cyzicus, a city on the Sea of Marmara. While the original work might have served as a votive offering in a sanctuary, the Roman copies adorned the villas and homes of the elite or were part of the sculptural decoration of public baths. In such settings, the group was meant to evoke a cheerful and erotic atmosphere.

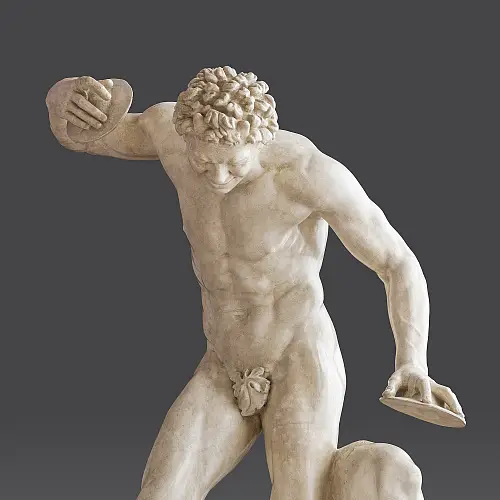

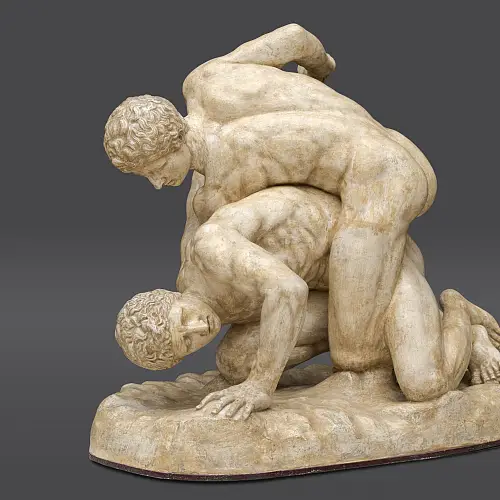

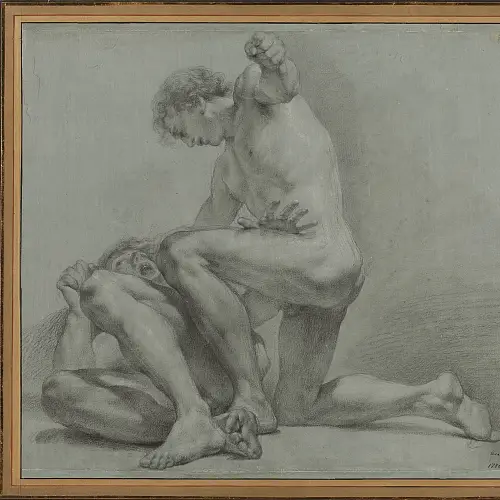

SFCol. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC playing the footclapper in Florence, the Medici Apollo, the Borghese Gladiator, the Florence Wrestlers The Uffizi Wrestlers, plaster cast, 1790, Mexico City, Antigua Academia de San Carlos (FAD/UNAM)Like other pieces in the collection of the Academia de San Carlos, the plaster cast of the Florentine Wrestlers is a copy of a copy of a copy! It was created in 1790 at the Academia de San Fernando in Madrid using a cast made by Anton Raphael Mengs ca. 1770 from a Roman marble group in the Uffizi in Florence (Inv. 216). It is likely that this sculpture itself originated from a lost Hellenistic bronze original. The Roman copy was discovered in 1583, along with a group of Niobids, in Rome, in the area of the Horti Lamiani, an ancient garden complex on the Esquiline Hill, and was acquired by the Medici family.

playing the footclapper in Florence, the Medici Apollo, the Borghese Gladiator, the Florence Wrestlers The Uffizi Wrestlers, plaster cast, 1790, Mexico City, Antigua Academia de San Carlos (FAD/UNAM)Like other pieces in the collection of the Academia de San Carlos, the plaster cast of the Florentine Wrestlers is a copy of a copy of a copy! It was created in 1790 at the Academia de San Fernando in Madrid using a cast made by Anton Raphael Mengs ca. 1770 from a Roman marble group in the Uffizi in Florence (Inv. 216). It is likely that this sculpture itself originated from a lost Hellenistic bronze original. The Roman copy was discovered in 1583, along with a group of Niobids, in Rome, in the area of the Horti Lamiani, an ancient garden complex on the Esquiline Hill, and was acquired by the Medici family.

The group, just under 90 cm in height, impresses with its intricate composition of athletes tightly intertwined in a struggle on the ground. It apparently represents the Greek pankration, a discipline that included both boxing and wrestling, where nearly everything was allowed – except biting and eye gouging.

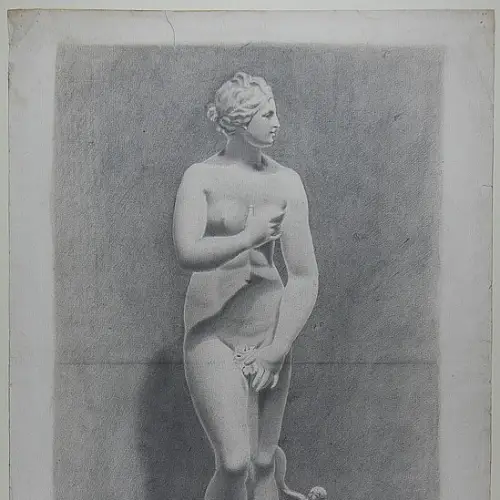

SFCol. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC , Venus de’ Medici Plaster cast of the Medici Venus, 1790, Mexico City, Antigua Academia de San Carlos (FAD/UNAM)The marble statue of Venus de' Medici, created around 100 BC (height 1.53 m), depicts the goddess of love in complete nudity. She presses her thighs together and modestly covers her breasts and between her legs, as if she were surprised by the viewer while bathing. At the same time, she turns her head to the left, with her long hair held by a band and tied into a knot at the nape. In front of the tree support on her left leg, a dolphin appears with two Erotes, who are clinging to its dorsal fin and tail.

, Venus de’ Medici Plaster cast of the Medici Venus, 1790, Mexico City, Antigua Academia de San Carlos (FAD/UNAM)The marble statue of Venus de' Medici, created around 100 BC (height 1.53 m), depicts the goddess of love in complete nudity. She presses her thighs together and modestly covers her breasts and between her legs, as if she were surprised by the viewer while bathing. At the same time, she turns her head to the left, with her long hair held by a band and tied into a knot at the nape. In front of the tree support on her left leg, a dolphin appears with two Erotes, who are clinging to its dorsal fin and tail.

The erotic aura of the goddess emphasizes her power in matters of love. This effect was likely heightened by the statue's original polychromy (coloring). The hair was gilded, and the lips were painted with cinnabar, as traces of color indicate. In addition, she once wore earrings. In her complete nudity and pose, the Venus Medici is in the tradition of the famous statue of Aphrodite, which the sculptor Praxiteles created around the middle of the 4th century BC for the sanctuary of the goddess in Knidos in Asia Minor.

Before reaching its current location at the Uffizi (Inv. 214), the sculpture was owned by the Medici family. It was likely discovered before 1550 in Rome, in the area of the Baths of Trajan on the Oppius, a spur of the Esquiline Hill. At an early stage, the Venus was combined with an ancient base, which bears the signature of a Greek artist but does not originally belong to the statue. This inscription is absent from the plaster cast in Mexico City. Numerous reproductions and adaptations of the statue and its type testify to its popularity since the Renaissance.

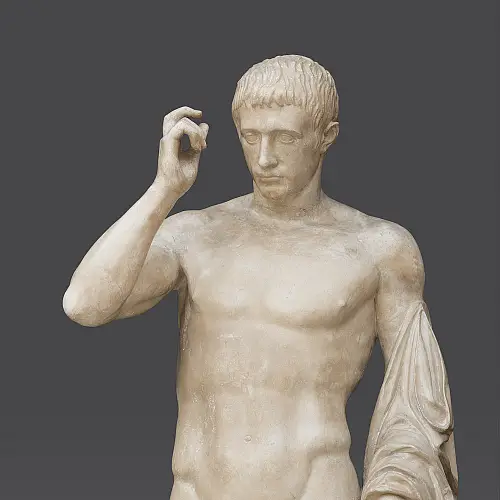

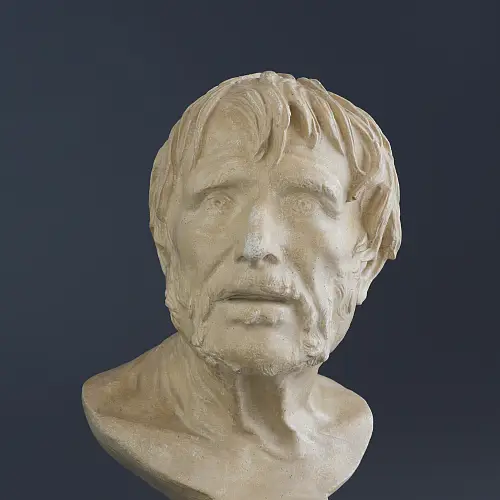

SFCol. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC , a “standing Hermes” (i.e. Mengs’ Hermes of the Pitti-Lansdowne Type), and the so-called Germanicus, now known as Marcellus as Hermes Logios, just to name a few. The collection of heads produced by Panucci included famous pieces such as Pseudo-Seneca, Pseudo-Vitellius, Farnese Hercules, Venus de’ Medici, the Florentine Niobe, as well as Homer, Sappho, Socrates, Antinous, and Nero, among others. Thus, the Mexican institution received a large collection of plaster casts of canonical marble works mainly from Rome, Naples, and Florence, which were represented by copies in the Academy of San Fernando because it had profited from gifts of the painter Anton Raphael Mengs Anton Raphael Mengs, Self-portrait, 1773, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, oil on panel, 93 x 73 cmhttps://de.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Mengs,_Selbstbildnis.jpg

, a “standing Hermes” (i.e. Mengs’ Hermes of the Pitti-Lansdowne Type), and the so-called Germanicus, now known as Marcellus as Hermes Logios, just to name a few. The collection of heads produced by Panucci included famous pieces such as Pseudo-Seneca, Pseudo-Vitellius, Farnese Hercules, Venus de’ Medici, the Florentine Niobe, as well as Homer, Sappho, Socrates, Antinous, and Nero, among others. Thus, the Mexican institution received a large collection of plaster casts of canonical marble works mainly from Rome, Naples, and Florence, which were represented by copies in the Academy of San Fernando because it had profited from gifts of the painter Anton Raphael Mengs Anton Raphael Mengs, Self-portrait, 1773, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, oil on panel, 93 x 73 cmhttps://de.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Mengs,_Selbstbildnis.jpg and the Spanish king Charles III. Camillo Paderni, Portrait of Charles VII/V of Naples and Sicily, in: Le Antichità di Ercolano esposte. Le pitture antiche d'Ercolano e contorni incise con qualche spiegazione. First Volume (Naples 1757), engravingCol. Biblioteca Nacional de México, Fondo Academia de San Carlos, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

and the Spanish king Charles III. Camillo Paderni, Portrait of Charles VII/V of Naples and Sicily, in: Le Antichità di Ercolano esposte. Le pitture antiche d'Ercolano e contorni incise con qualche spiegazione. First Volume (Naples 1757), engravingCol. Biblioteca Nacional de México, Fondo Academia de San Carlos, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC in the preceding years.

in the preceding years.

The marble statue measures 1.73 meters in height (excluding the plinth) and includes several modern additions, such as the wings on the head. Since other Roman replicas of the same design have survived ("Hermes Pitti-Lansdowne type"), it is certainly a copy of a lost Greek original, which can stylistically be dated to the High Classical period, presumably a bronze statue of the second half of the 5th century BCE. This statue depicted the messenger god as a youthful figure, with the left leg bearing his weight and the right leg relaxed, while the left arm was extended. Only the left shoulder and upper arm were covered by a cloak. His head showed idealized features and gazing downward to the lower left side. The original attributes of this representation of Hermes are uncertain, but he may have held a kerykeion or caduceus (messenger's staff) in his left hand.

In Rome and Italy, this statue type was occasionally combined with the portraits of non-imperial individuals. It appears that such portraits featuring divine bodies were set up in funerary contexts.

SF Col. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

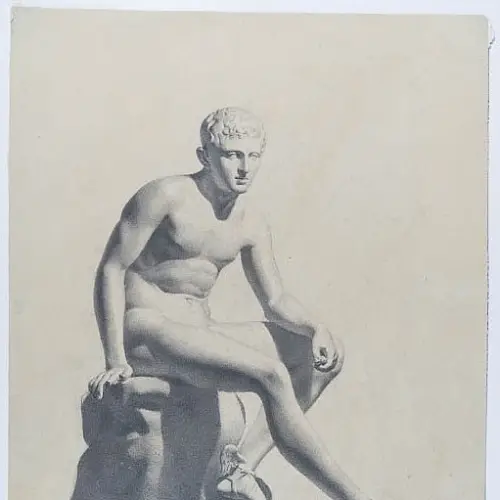

As regards the idealized body of the portrait, the sculptor adopted a classical statue type ("Hermes Ludovisi type"). This is characterized by a muscular body in a contrapposto stance, with the right hand raised. A cloak is draped over the slightly bent left arm. At the left foot lies a tortoise, on whose shell the artist, Cleomenes of Athens, inscribed his signature.

Already while displayed in Versailles, molds must have been taken from the sculpture, because as early as 1790, Josef Panucci used the existing copy at the Academia de San Fernando in Madrid to create the cast of the Mexican institution.

SF Col. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

Panucci listed the costs of creating the plaster casts. Unsurprisingly, the most expensive piece was the Laocoön and his Sons Group of Laocoon, plaster cast, 1790, Mexico City, Antigua Academia de San Carlos (FAD/UNAM)The original Laocoön group has been in the Vatican Museums since its discovery on the Oppian Hill in Rome more than 500 years ago. The sculpture was made of marble in the late 1st century BCE and depicts the Trojan priest Laocoön and his two sons being attacked at an altar by two giant serpents. The animals coil around the arms and legs of their victims, binding them together in this way. The boys and their father are arranged in a single plane. This leads to a single perspective from which the dramatic scene can be perceived. According to the mythological tradition, made famous above all by Virgil's Aeneid (Book 2.40-56; 199-234), Laocoön is a priest of Apollo or Poseidon. The suffering that befalls him and his sons is explained in various ways in ancient literature. According to one tradition, Laocoön enraged Apollo by having intercourse in front of his cult statue (according to the Hellenistic author Euphorion, as quoted by Virgil's commentator Servius: ad Aen. 2.201), or that he warned his fellow citizens about the danger of the Trojan Horse against the will of the gods (cf. Virgil, Aen. 2.199-234). One message of the group is that not even by retreating to the altar the father and his sons can be saved from divine power. In this way, the ancient spectator was confronted with the helplessness of human existence in the face of greater forces.

The original in the Vatican can be identified with a group that Pliny the Elder mentions around 70-79 CE in a residence of the Flavian prince Titus (Plin. nat. 36.37). According to him, Laocoön is an exceptional work by the sculptors from Rhodes Hagesandros, Polydoros, and Athenadoros. The Roman author seems to suggest that it was made from a single block of marble, but in reality, the three artists assembled it from at least seven pieces, with the joints carefully concealed. Originally, the right arm of the central figure was bent, as is demonstrated by a fragment rediscovered only in 1903 by the archaeologist and art dealer Ludwig Pollak in a stonemason’s workshop on the Esquiline Hill. Therefore, the copy created around 1790 in the Academia de San Carlos includes the old restauration showing an extended arm.

As a masterpiece of ancient sculpture and a valuable possession of the papal collections, the artwork has exerted an enormous artistic and scholarly impact in Europe and beyond since the early modern period. The expressive visual language inspired numerous painters and sculptors to engage with the sculpture. Copies in bronze and marble served as ornaments for palaces and gardens. Additionally, plaster casts were used as models in academic drawing classes. Especially in the Age of Enlightenment and Neoclassicism, i. e. the 18th century, the group became the focal point of aesthetic theories developed by intellectuals such as Johann Joachim Winckelmann and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing.

SFCol. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC , which cost 600 Reales; the Apollo of Belvedere cost 300 Reales, while the price of the so-called Dying Gladiator, i.e. the Dying Gaul, was 250 Reales. The total production and packaging cost was over 235,000 Reales and included the materials for 173 measures of straw, tow, sand, nails, and paper. Panucci completed the order in August 1790 and received 23,543 Reales for his work. The plaster casts were packed into 63 wooden boxes that cost another 4,498 Reales.

, which cost 600 Reales; the Apollo of Belvedere cost 300 Reales, while the price of the so-called Dying Gladiator, i.e. the Dying Gaul, was 250 Reales. The total production and packaging cost was over 235,000 Reales and included the materials for 173 measures of straw, tow, sand, nails, and paper. Panucci completed the order in August 1790 and received 23,543 Reales for his work. The plaster casts were packed into 63 wooden boxes that cost another 4,498 Reales.

The cargo was ready in September 1790. A dozen horse-drawn carts transported it from Madrid to Cádiz, accompanied by Manuel Tolsá. Together with the sculptor, the cargo of crates set sail for Havana on the Royal Navy ship Santa Paula on February 20, 1791, a vessel of the Real Armada that ensured the safe passage and protection from pirates who plagued commercial routes at the time. Once in Cuba, the ship was accompanied by the Minerva, also from the Real Armada, to the port of Veracruz.

The sculptures were unpacked and verified by Tolsá in Veracruz. 29 days after their arrival in the Americas, they were packed again in preparation for the 400 kilometre-long journey by mule to Mexico City, their final destination (arriving after 15 days). Since the objects were damaged during transportation, they were professionally restored by Tolsá himself and two assistants.

EA

Academic Drawing

Artistic Training at the Academia de San Carlos

In 1791, Manuel Tolsá brought almost 200 plaster casts along with him from Spain when he took up his post as Director of Sculpture at the newly founded Academia de San Carlos. Already in the founding statutes of the colonial institution (1784/1785), drawing skills were emphasized as essential to the training of students. Copies of prominent ancient and modern works served as models. This was informed by the cultural-political intention of the Spanish government to promote neo-classicist art forms in accordance with the ideals of the Enlightenment which were to replace the Baroque tradition. At the same time, the academic training was intended to break the influence of both the church and the traditional guilds on the arts and crafts.

The erotic aura of the goddess emphasizes her power in matters of love. This effect was likely heightened by the statue's original polychromy (coloring). The hair was gilded, and the lips were painted with cinnabar, as traces of color indicate. In addition, she once wore earrings. In her complete nudity and pose, the Venus Medici is in the tradition of the famous statue of Aphrodite, which the sculptor Praxiteles created around the middle of the 4th century BC for the sanctuary of the goddess in Knidos in Asia Minor.

Before reaching its current location at the Uffizi (Inv. 214), the sculpture was owned by the Medici family. It was likely discovered before 1550 in Rome, in the area of the Baths of Trajan on the Oppius, a spur of the Esquiline Hill. At an early stage, the Venus was combined with an ancient base, which bears the signature of a Greek artist but does not originally belong to the statue. This inscription is absent from the plaster cast in Mexico City. Numerous reproductions and adaptations of the statue and its type testify to its popularity since the Renaissance.

SF Col. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

The didactic significance of the plaster casts as models is reflected in more than 5,000 surviving drawings produced between the late 18th and the early 20th century. In the first decades after the academy was founded, the curriculum consisted of four sections: First, students had to learn to draw individual body parts based on graphic models.

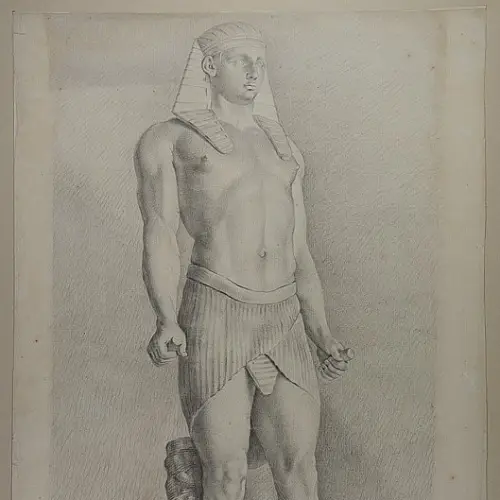

Next, natural objects and sculptures were likewise copied from engravings, too. Third, plaster casts were used as models whose three-dimensional effect in space had to be reproduced using light and shadow effects. The final step was to draw from living models (all of whom were male until well into the 19th century). It is not surprising that canonical works such as the Apollo Belvedere, the Hermes at Rest from Herculaneum, the Venus de’ Medici, or the Ildefonso Group were the preferred models in the first phase of the academy. Some of the early drawings are still characterized by baroque-expressive forms.

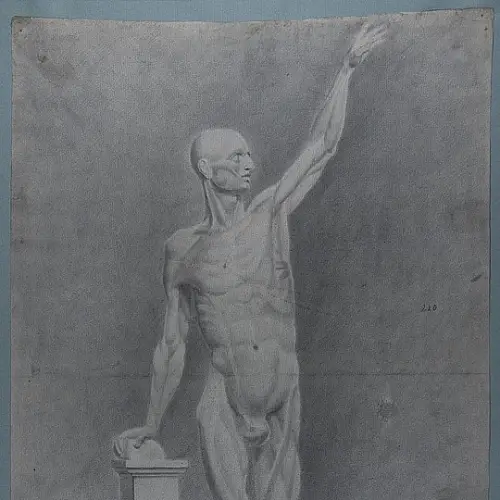

In the later 18th century, sculptors like Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828) created Écorchés as models for artists. Corresponding to plaster casts of famous sculptures, they were intended to help aspiring painters and sculptors achieve the ideal of naturalistic representation. In line with Neoclassicism, this also involved a return to ancient design principles, as shown by the ,muscle man' at the Academia de San Carlos, whose pose recalls the statue of the Borghese Fighter.

SF Col. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

For the period from 1778 to 1821, a considerable number of ca. 4,000 students has been recorded who ideally spent around twelve years at the academy. There were 16 scholarships at the academy for aspiring painters, sculptors, architects and engravers from underprivileged backgrounds; some people from indigenous backgrounds were also admitted. However, by no means all those who attended drawing courses aspired to a career as fine artists or architects. Rather, the classes were seen as a basis for training for all kinds of professions.

VFM

Jerónimo Antonio Gil

Engraver and Founding Director of the Academia de San Carlos

Jerónimo Antonio Gil, a distinguished member of the Academia de San Fernando, played a key role in the spread of classicist ideas in New Spain and in the founding of the American Academy and its immediate predecessors, the School of Engraving (1778) and the Provisional Drawing School (1781). On March 15, 1778, King Charles III Francisco Tomás Prieto, Medal with portrait of Charles III of Spain, 1770 (plaster cast, 1790, Antigua Academia de San Carlos, FAD/UNAM), 21.5 x 17 cmCol. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC announced by royal decree his decision to appoint Gil as chief engraver (Grabador mayor) of the Royal Mint of Mexico and to commission him to found a school of engraving to train qualified craftsmen.

announced by royal decree his decision to appoint Gil as chief engraver (Grabador mayor) of the Royal Mint of Mexico and to commission him to found a school of engraving to train qualified craftsmen.

Gil was born in Zamora, Spain, in 1731 and died in Mexico City in 1798. He came to Madrid in 1751 with the intention of studying painting; he studied drawing and sculpture with Felipe Castro for three years and then went to the workshop of Luis González Velázquez for a further two and a half years. In 1753, he applied unsuccessfully for a painting competition at the Academy of San Fernando Madrid, Facade of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, situated in the Palacio de GoyenecheCol. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid . Due to financial constraints, he participated in a competition for plate and intaglio engraving the following year. Gil won one of the places for seal engraving under the guidance of his teacher Tomás Francisco Prieto and thus became one of the first members of this class at the institution.

. Due to financial constraints, he participated in a competition for plate and intaglio engraving the following year. Gil won one of the places for seal engraving under the guidance of his teacher Tomás Francisco Prieto and thus became one of the first members of this class at the institution.

Together with the artist Francisco Javier de Santiago Palomares, he created a collection of typefaces for the Real Imprenta of Madrid and engraved seals and plates for various printed works as well as numerous medals and portraits of his royal patron, King Charles III, and other important personalities. His academic and artistic merits earned him the important appointment of Tallador Mayor de la Casa de Moneda (Chief Engraver of the Royal Mint) in New Spain.

CAROLO III PIO POTENTISSIMO HISPANIARUM REGI SEMPER AUGUSTO – SIGNUM HOC PIETATIS ET OBSERVANTIAE CUDI FECIT 1791 / MEXICANA D[IVI] C[AROLI] ACADEMIA QUOD IPSAM AUCTORITATE SUMPTIBUS EREXERIT INFORMARIT. / H[ieronymus] A[ntonius] GIL

The Mexican Academy of San Carlos engraved in 1791 this symbol of care and respect for Charles III, the pious and mighty king of Spain, the ever sublime, because he himself built it and designed it [i. e. the Academy] with his power and resources. Jerónimo Antonio Gil

VFM Col. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

Together with his two sons and three assistants, Gil set off for America in 1778 and arrived at the port of Veracruz on December 5 of the same year aboard the ships Nuestra Señora del Rosario and San Francisco de Asís. In his luggage he had 24 wooden crates with personal belongings and teaching materials for the Casa de Moneda and the school of engraving he was to found. For his trip to New Spain, he selected outstanding works from Madrid's collections. Gil selected pieces from the sulphur casts of ancient gems that he had acquired some time earlier in Italy.

He also brought books, including Gérard Audran's treatise ,The proportions of the human body: measurements of the most beautiful statues of antiquity' (Les proportions du corps humain, mesurées sur les plus belles figures de l'Antiquité, Paris, 1638), which Gil translated into Spanish (Madrid 1780), as well as drawings, prints, a collection of coins and medals and tools. In addition, Gil's cargo apparently contained the plaster casts of several heads, although only four or five of the original eight heads remained: “everything else fell to pieces along the way,” as Gil noted after his arrival. The so-called Cicero appears to have been one of these very early imports.

VFM https://cloud10.todocoleccion.online/libros-segunda-mano/tc/2022/10/31/21/371753766.jpg

Due to the success of Gil's school of engraving at the Royal Mint, a petition was submitted to the Spanish Viceroy Martín de Mayorga y Ferrer to establish a separate Academy of Fine Arts in Mexico, modeled on the Academia de San Fernando in Madrid. After Mayorga had given his preliminary approval, the officials involved took care of the objectives, administrative structure, financing and staff of the new institution. The Academy of San Carlos was officially founded on Christmas Day of 1783 through a decree of Charles III, and the official inauguration took place on November 4, 1785. Gil was appointed Director General for life.

EA

Manuel Tolsá

Sculptor, Painter, and Architect

EA/VFM MUNAL/INBAL

Manuel Tolsá Sarrión was born in Enguera (Spain) in 1757 and died in Mexico City in 1816. Trained at the Real Academia de las Artes de San Carlos in Valencia and at the Academia de San Fernando in Madrid, he began a career as a sculptor in Spain in the 1780s. In 1790 he was awarded the post of director of sculpture at the Academia de San Carlos. Before his departure, he assembled a large number of plaster casts of Graeco-Roman sculptures at the Academia de San Fernando for his new place of work, which he brought with him to Mexico and which formed the actual core of the Academy's collection.

Together with Jerónimo Antonio Gil, Antonio González Velázquez and later Rafael Ximeno, Tolsá trained a new generation of budding artists and architects at the academy who were needed in many places, like in the royal mint or in urban construction in New Spain. Tolsá himself is credited with the completion of Mexico City Cathedral and the construction of the building now known as the Palacio de Minería (Mining Palace). He also designed the Hospicio Cabañas in Guadalajara (originally called Casa de la Misericordia) as well as several altars in churches in Mexico City, Puebla and Veracruz. His architecture is characterized by classical forms, but has a distinctive appearance due to the use of local materials.

VFM https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palacio_de_Miner%C3%ADa#/media/Datei:Palacio_de_Miner%C3%ADa._Plaza_Manuel_Tols%C3%A1.JPG

VFM https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hospicio_Caba%C3%B1as#/media/Datei:Hospicio_caba%C3%B1as.JPG

His name is primarily associated with the creation of the bronze equestrian statue of Charles IV (El Caballito), which was commissioned in 1795 on the initiative of the Viceroy Marquis of Branciforte and inaugurated on December 9, 1803 in the Plaza Mayor, the central square of Mexico City, now known as the Zócalo. Modelled on the famous statue of Marcus Aurelius in the Capitol Square in Rome, the sculptor created a work that represented the imperial rule of the Bourbons over New Spain. During his visit to Mexico City, Humboldt, who attended the inauguration of the sculpture, praised the “beauty and purity” of the style of the thirteen-ton statue which “with the exception of Marcus Aurelius in Rome [...] surpasses anything we possess in this field throughout Europe”. The square itself was redesigned for the monument according to the Roman model of the Piazza del Campidoglio which Michelangelo designed in 1546. Today, El Caballito adorns the square in front of the Palacio de Minería.

VFM blob:null/aa801719-ffe1-47e8-920a-f55f62331e7c

After Mexico's Independence, and in spite of anti-Spanish sentiments, it was decided to preserve the statue for its artistic value. It was moved to the patio of the old University of Mexico in 1824. In 1852, it was decided to move it again, this time to Paseo de la Reforma, where it was meant to function as an urban ornament. However, in 1979, due to the increase of car traffic and the widening of the avenue, it was finally decided to place it in a square created for it in front of the Mining Palace and the National Museum of Art. Since then, ,El Caballito' has adorned the Manuel Tolsá Plaza on Tacuba Street in downtown Mexico City.

VFM https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equestrian_statue_of_Charles_IV_of_Spain#/media/File:El_caballito_de_Tolsa_a.jpg

VFM

Vitruvius, Vasari and Winckelmann

The library of the Academia de San Carlos

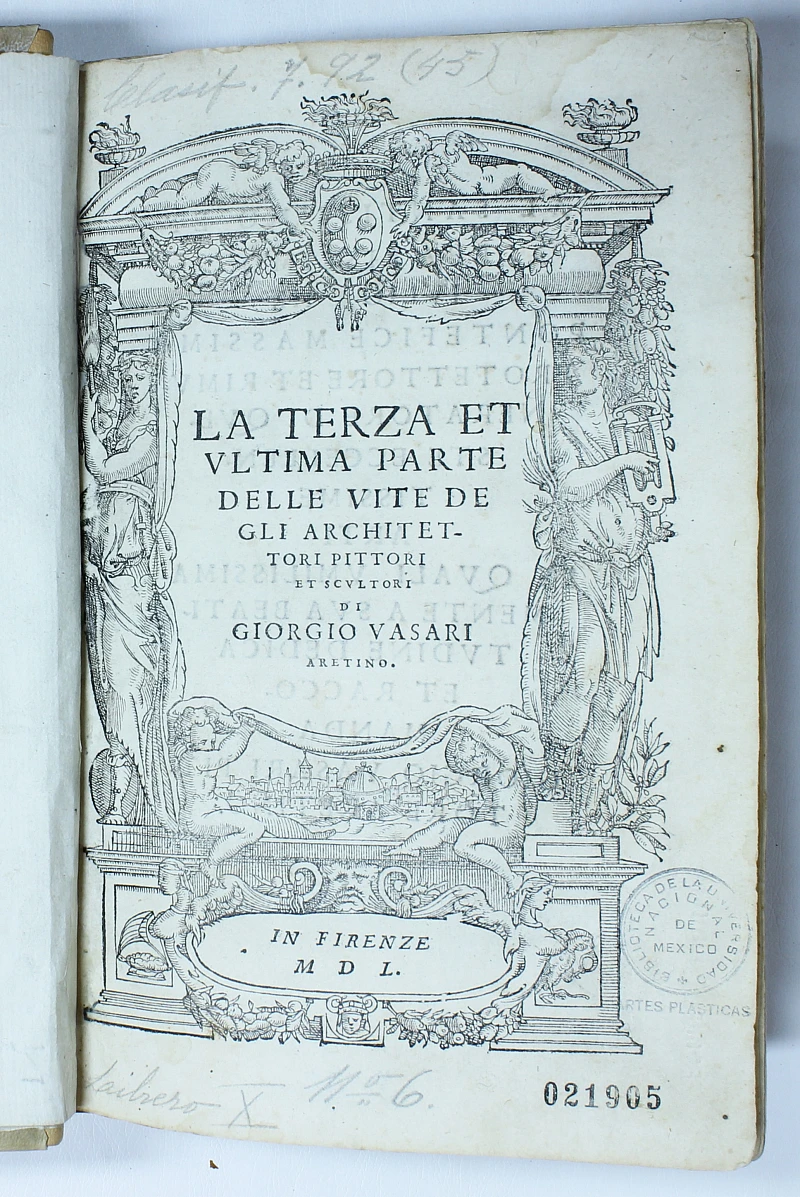

The first edition in three volumes dates back to 1550 (an exemplar of the third one has survived in the National Library of Mexico), although in the 16th century alone, the work reached about five editions, and its influence in the Western world has been immense. Not only is it a paradigmatic compilation of artistic biographies, being an invaluable primary source on the life and work of early Italian artists, but also the author’s reflections on the role of Florence and Rome in the development of the Renaissance, as well as his considerations on the medieval past (including the coining of the term “Gothic”), are fundamental (although today, undoubtedly, partly debatable). The work was translated into most European languages and, as evidenced by the copy preserved in Mexico, its impact went beyond the borders of the Old World.

VFM Col. Biblioteca Nacional de México, Fondo Academia de San Carlos, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

DiDuring the Spanish colonial period, the Academia de San Carlos housed an extensive library comprising several hundred volumes, the holdings of which are now kept in various institutions such as the Mexican National Library (Biblioteca Nacional de México). Graduates of the Academia de San Fernando in Madrid, in particular, who were appointed as lecturers at the young Mexican institution, including the engraver Jerónimo Antonio Gil and the sculptor Manuel Tolsá , as well as the engraver José Joaquín Fabregat and the painter Rafael Ximeno y Planes, were responsible for its development in the late 18th century. In addition, the mathematician and physician José Ignacio Bartolache, who was born in New Spain, took care of the library as the Academy’s secretary (1782-1790). However, it is not always possible to determine which books came to Mexico City at what time. One possible source of supply during the founding period was the English ship Westmorland, which was captured by the French off the coast of Livorno (Italy) in 1778 and brought to the port of Malaga, i.e. to Spain which at the time was at war with England. Its rich cargo, acquired from English Grand Tour aristocrats in Italy, contained numerous crates of works of art and 400 books. The cargo was purchased by Charles III for the Madrid Academy and distributed from there to various institutions, from which the Academia de San Carlos may also have benefited.

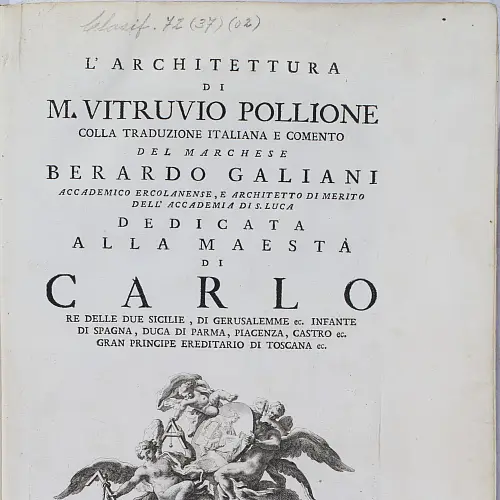

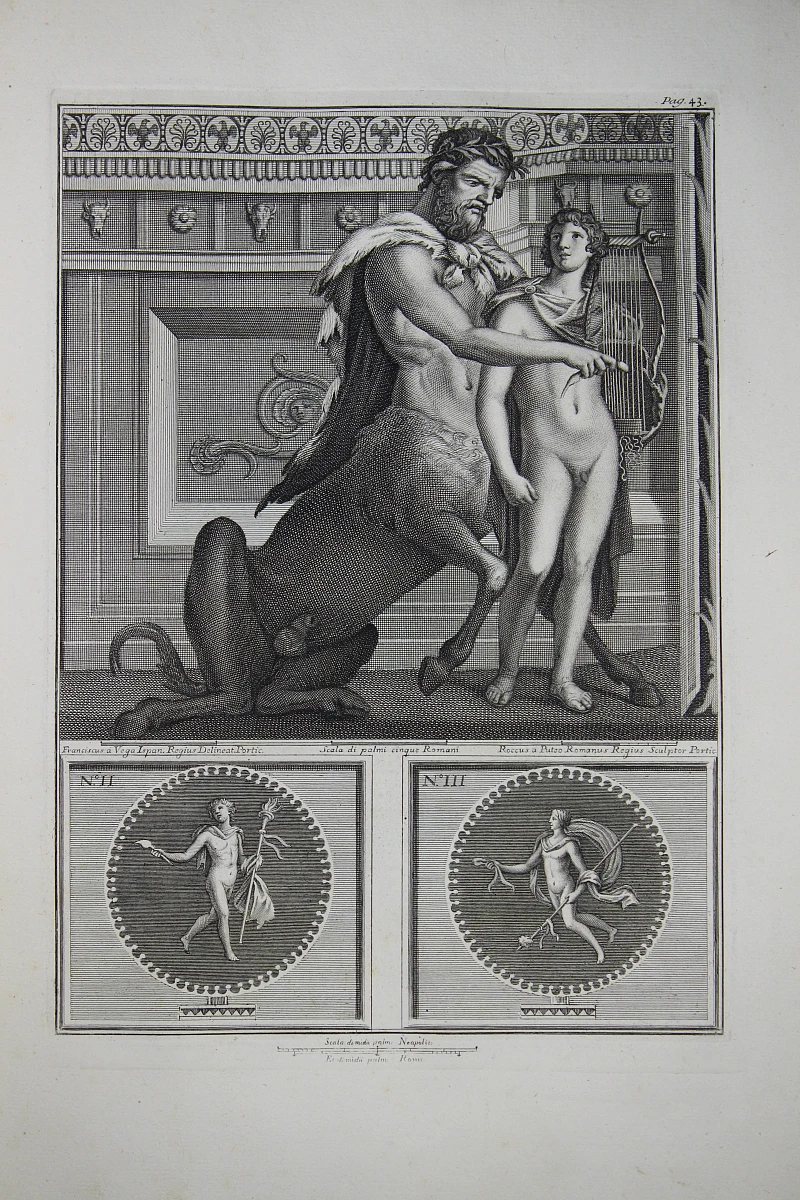

However, its relevance grew even more during the Age of Enlightenment, due to the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum, as well as the discovery of new codices containing the Vitruvian text. The translation of De architectura by Berardo Galiani (1724-1774) became one of the most influential works of the 18thand even 19th centuries. This author and theoretician of the Kingdom of Naples not only edited the Latin text, collating previously unknown Vatican codices, but also offered a modern Italian translation, enriched with abundant notes and 25 engravings. These illustrations, made by Galiani himself, stand out for their high artistic quality, demonstrate the profound philological rigor of the author and are, therefore, an excellent example of the spirit of enlightenment. The first edition of this work was published in Naples in 1758, from which the copy preserved in Mexico comes.

Galiani's intellectual qualities are evident when considering that he was a member of the most prestigious academies in Italy in the fields of letters, arts and archeology. These include the Accademia della Crusca (Florence), the Accademia di San Luca (Rome) and the Accademia Ercolanese (Naples). As a member of the latter, Galiani personally accompanied Johann Joachim Winckelmann during the excavations of the Herculaneum theater. The controversy between the two of them regarding the development of these excavations is famous, although they finally managed to reconcile. After Galiani's death in 1774, Tsarina Catherine II of Russia acquired his valuable library, which was transferred to St. Petersburg, where it is preserved together with the libraries of other great intellectuals of the Enlightenment, such as Denis Diderot and Voltaire.

VFM Col. Biblioteca Nacional de México, Fondo Academia de San Carlos, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

The publications in the Mexican library came primarily from European publishing houses. They were written in all sorts of languages (Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, German, English, Latin). However, a few books and manuscripts published in New Spain have also survived.

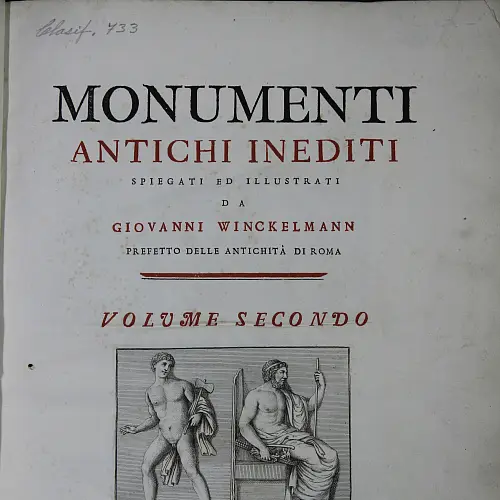

The oldest work is probably Giorgio Vasari's artist biographies (Le Vite) from 1550 (Florence); an early edition of Vitruvius from the Spanish Alcalá de Henares near Madrid (1582) has also survived. In terms of quantity, however, contemporary books from the 18th century predominated. In line with the ideals of the Enlightenment, they were intended to provide budding artists with a theoretical basis for their work. Accordingly, there are many publications on art and architectural theory, arts and crafts and the study of antiquity. The writings of Anton Raphael Mengs and Johann Joachim Winckelmann were represented, as were Piranesi's famous prints and the volumes of the Accademia Ercolanese containing the results of the Bourbon excavations in Pompeii and Herculaneum (e.g. Le Antichità di Ercolano Esposte, Naples, 1757-1792) as well as Berardo Galiani's annotated translation of Vitruvius from 1758 (Naples) which was dedicated to Charles III. However, the collection also contained books on subjects of technology, natural sciences (astronomy, zoology, botany) and mathematics (from Euclid to Sir Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica).

SF

A Naturalist at the Academy of Fine Arts

Alexander von Humboldt in Mexico

VFM https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a2/Rafael_Ximeno_y_Planes_-_Retrato_de_Alexander_Von_Humboldt.jpg, Foto: Luis Alvaz

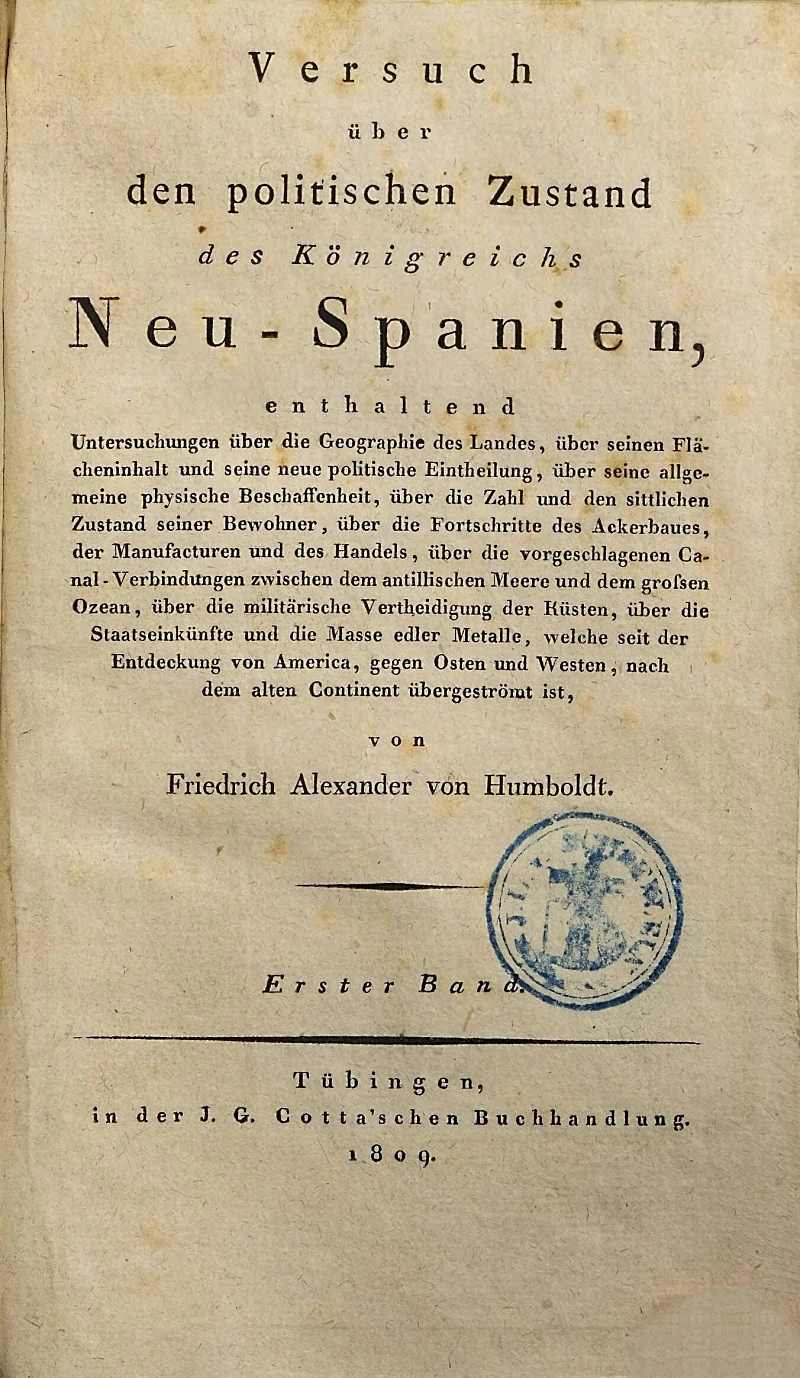

When the explorer and natural scientist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) visited Mexico City in 1803, he was positively impressed by the appearance of the streets and squares. The journey through the Spanish colonial territory formed the basis for his ,Essay on the political state of the Kingdom of New Spain' (Versuch über den politischen Zustand des Königreichs Neu-Spanien) which was published in five volumes between 1809 and 1812 and is dedicated to Charles IV of Spain.

The treatise deals with the geography, political organization, and socio-economic conditions of New Spain. In the first volume, the scholar also discusses the country's scientific institutions, praising the young Academy of Fine Arts: “The government has provided a spacious building here in which there is a far more beautiful and complete collection of plaster casts than can be found anywhere in Germany.” Humboldt is also “astonished at how the Apollo Belvedere, the Laocoon Group and other even more colossal statues could be transported over mountain paths that are at least as narrow as those of St. Gotthard,” and he emphasizes the high cost of producing the casts.

He also suggested that the pre-Columbian antiquities he had seen during his visit to the academy, which reminded him of Egyptian and Hindu art, should be exhibited alongside the Graeco-Roman sculptures. This demand, which seems very modern, demonstrates the comprehensive approach of the enlightened researcher who compares different cultures and their pictorial testimonies with one another. Elsewhere, he even contrasts the continuous depiction on the sacrificial stone of the Aztec ruler Tízoc (found in 1791) with the frieze on Trajan's Column in Rome. Regardless of such approaches, Humboldt had no doubt about the special status and exemplary nature of Greco-Roman antiquity; in this he proved to be a follower of classicism as it was propagated by Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Accordingly, in his Essay, he ascribes an important function to the casts at the Academy in the dissemination of “good taste and beautiful forms.” Humboldt also praised the fact that artists and craftsmen from a lower class or indigenous background were also trained at the institution, in keeping with the spirit of the Enlightenment.

VFM Col. FAD-UNAM, Foto: CIDYCC, AASC

"None of the cities of the new continent, not even those of the United States, is in possession of such large and firmly established scientific institutions as the capital of Mexico. I will mention here only the mining school, which is under the direction of the learned d'Elhuyar [Fausto Fermín Delhuyar, active in Mexico from 1788 to 1821, TN], and to which we will return in the mining and metallurgy section, the botanical garden, and the academy of painting and sculpture. The latter is called the Academia de las Nobles Artes de México and owes its existence to the patriotism of several private Mexican citizens and the protection of Minister Gálvez. The government has provided a spacious building here in which there is a far more beautiful and complete collection of plaster casts than can be found anywhere in Germany. One is amazed at how the Apollo Belvedere, the Laocoon Group and other even more colossal statues could be brought over mountain paths that are at least as narrow as those of St. Gotthard, and is no less surprised to see the masterpieces of antiquity united under the hot zone and on a plateau that is even higher than the monastery on the great St. Bernard. This collection of plaster casts cost the king close to 200,000 francs. The remains of Mexican sculpture, the colossal statues of basalt and porphyry which are covered with Aztec hieroglyphics and bear some resemblance to the style of the Egyptians and Hindus, should be collected in the academy building, or rather in one of the courtyards belonging to it; for it would certainly be curious to see these monuments of the first civilization of our species, these works of a semi-barbarian people who inhabited the Mexican Andes, next to the beautiful forms that were born under the skies of Greece and Italy.

The income of the Academy of Fine Arts in Mexico amounts to 125,000 francs, of which the government contributes 60,000, the Corps of Mexican Miners close to 25,000, and the Consulado, or the Trade Guild of the capital, over 15,000. The current influence of this institution on the taste of the nation is undeniable, and it can be seen especially in the arrangement of the buildings, the perfection with which the stones are carved, the decorations of the capitals and the reliefs in stucco work. What beautiful buildings are to be found in Mexico, and even in provincial towns such as Guanajuato and Queretaro! These works, which often cost a million to a million and a half francs, could be displayed in the most beautiful streets of Paris, Berlin or St. Petersburg. Mr. Tolsá, professor of sculpture in Mexico, has even cast a statue of Carl IV on horseback which, with the exception of Marcus Aurelius in Rome, surpasses in beauty and purity of style anything we have in this field throughout Europe. All instruction in the academy is given free of charge, and is not confined to the drawing of landscapes and figures, but has been sensible enough to use it in other ways to stimulate the national industry. Every evening a few hundred young people gather in the large halls, splendidly lit by Argand lamps, some of whom draw from casts or live models, while others copy outlines of furniture, candelabra and other bronze ornaments. Here (which in a country where the prejudices of the nobility against the castes are so deeply rooted) class, color and human race are completely mixed, and one sees the Indian or Métis next to the white man, and the son of a poor craftsman competing with the children of the great lords of the country. It is truly comforting to see how the culture of the sciences and arts introduces a certain equality among men in all zones, making them forget, at least for a time, the petty passions whose effects prevent social happiness."

SF

Further reading on the themes of the exhibition

· T. A. Brown, La Academia de San Carlos de la Nueva España (Mexico City 1976).

· E. Báez Macías, Jerónimo Antonio Gil y su traducción de Gérard Audran (Mexico City 2001).

· E. Báez Macías, Historia de la Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes (antigua Academia de San Carlos) 1781-1910 (Mexico City 2009).

· C. Bargellini – E. Fuentes, Guía que permite captar lo bello. Yesos y dibujos de la Academia de San Carlos 1778-1916 (Mexico City 1989).

· S. Dean-Smith, ‘A Natural and Voluntary Dependence’. The Royal Academy of San Carlos and the Cultural Politics of Art Education in Mexico City, 1786-1797, Bulletin of Latin American Research 29/3, 2010, 278-295.

· K. Donahue-Wallace, Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521-1821 (Albuquerque 2008).

· K. Donahue-Wallace, Jerónimo Gil and the Idea of Spanish Enlightenment (Albuquerque 2017).

· S. Faust – V. Flores Militello, Laokoon in Mexiko. Die Academia de San Carlos in Mexiko-Stadt und Amerikas älteste Gipsabguss-Sammlung, Antike Welt 52/4, 2021, 84-87.

· O. H. Flores Flores, Neoclassical taste and antiquarian scholarship. The Royal Academy of the Three Noble Arts of San Carlos of Mexico, Alexander von Humboldt and Pedro José Márquez, in: N. Temple – A. Piotrowski – J. M. Heredia (Hrsg.), The Routledge Handbook on the Reception of Classical Architecture (London 2020) 110-134.

· O. H. Flores Flores, Verbreitung und Rezeption des Klassizismus in Mexiko (1783-1866). Anmerkungen zu Winckelmann in der Neuen Welt, Stendaler Winckelmann-Forschungen 14 (Petersberg 2023).

· E. Fuentes-Rojas, Art and Pedagogy in the Plaster Cast Collection of the Academia de San Carlos in Mexico City, in: R. Frederiksen – E. Marchand (Hrsg.), Plaster Casts. Making, Collecting and Displaying from Classical Antiquity to the Present (Berlin 2010) 229-247.

· A. C. Hamman – S. G. Widdifield, The Royal Academy of San Carlos, 1871-1800, in: J. F. Lopez (Hrsg.) A Companion to Viceregal Mexico City (Leiden 2021) 440-466.

· A. Laird, The epic of America: An introduction to Rafael Landívar and the Rusticatio Mexicana (London 2006).

· A. Laird, Aztec Latin. Renaissance Learning and Nahuatl Traditions in Early Colonial Mexico (Oxford 2023).

· J. Maier Allende, Karl Bourbon Farnese, König und Archäologe. Die Anfänge der modernen Archäologie im Königreich beider Sizilien, Akzidenzen 20 (Stendal 2014).

· A. Negrete Plano, La donación de los vaciados de Mengs a la Academia, Academia. Boletín del la Real Academia de San Fernando 100/101, 2005, 169-184.

· A. Negrete Plano, Anton Raphael Menhs y la Antigüedad (Madrid 2013).

· V. Sampaolo (Hrsg.), Carlo di Borbone e la diffusione delle antichità (Milano 2016).

· O. E. Vázquez, Drawing, Copying and Pedagogy in Mexico’s and Brazil’s Art Academies, in: N. Nanobashvili – T. Teutenberg (Hrsg.), Drawing Education – Worldwide! Continuities – Transfers – Mixtures (Heidelberg 2019) 203-214.